the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Daytime low-level clouds in West Africa – occurrence, associated drivers, and shortwave radiation attenuation

Derrick K. Danso

Sandrine Anquetin

Arona Diedhiou

Kouakou Kouadio

Arsène T. Kobea

This study focuses on daytime low-level clouds (LLCs) that occur within the first 2 km of the atmosphere over West Africa (WA). These daytime LLCs play a major role in the earth's radiative balance, yet their understanding is still relatively low in WA. We use the state-of-the-art ERA5 dataset to understand their occurrence and associated drivers as well as their impact on the incoming surface solar radiation in the two contrasting Guinean and Sahelian regions of WA. The diurnal cycle of the daytime occurrence of three LLC classes namely No LCC, LLC Class-1 (LLCs with lower fraction), and LLC Class-2 (LLCs with higher fraction) is first studied. The monthly evolutions of hourly and long-lasting LLC (for at least 6 consecutive hours) events are then analyzed as well as the synoptic-scale moisture flux associated with the long-lasting LLC events. Finally, the impact of LLC on the surface heat fluxes and the incoming solar irradiance is investigated. During the summer months in the Guinean region, LLC Class-1 occurrence is low, while LLC Class-2 is frequent (occurrence frequency around 75 % in August). In the Sahel, LLC Class-1 is dominant in the summer months (occurrence frequency more than 80 % from June to October); however the peak occurrence frequency of Class-2 is also in the summer. In both regions, events with No LLC do not present any specific correlation with the time of the day. However, a diurnal evolution that appears to be strongly different from one region to the other is noted for the occurrence of LLC Class-2. LLC occurrence in both regions is associated with high moisture flux driven by strong southwesterly winds from the Gulf of Guinea and significant background moisture levels. LLC Class-2 in particular leads to a significant reduction in the upward transfer of energy and a net downward energy transfer caused by the release of large amounts of energy in the atmosphere during the cloud formation. In July, August, and September (JAS), most of the LLC Class-2 events may likely be the low-level stratiform clouds that occur frequently over the Guinean region, while they may be deep convective clouds in the Sahel. Additionally, LLC Class-2 causes high attenuation of the incoming solar radiation, especially during JAS, where about 49 % and 44 % of the downwelling surface shortwave radiation is lost on average in Guinea and the Sahel, respectively.

- Article

(10985 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(10382 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

In West Africa (WA), the prediction of key features of the climate such as the West African Monsoon (WAM) is known to have large uncertainties (Christensen et al., 2013). Most of the uncertainties are essentially linked to the inability of climate models to efficiently represent convection and cloudiness, in particular low-level clouds (LLCs) (Hannak et al., 2017). Climate models struggle to properly reproduce the planetary boundary layer above the ocean and the continental surface as well as the land–ocean flux gradients that drive the triggering and the variability of LLC systems. These clouds and their temporal variation strongly influence the reflectivity of the atmosphere. As a result, large uncertainties exist in the prediction of surface solar radiation in the region (Knippertz et al., 2011). In the light of the recent increased interest in solar energy projects in WA (World Bank, 2019) after the Paris Agreement in 2015, the predictability of surface solar radiation (Armstrong and Hurley, 2010; Kosmopoulos et al., 2015) thus remains a key issue for any feasibility study concerning solar energy during either dry or wet seasons in the region.

WA is characterized by a frequent occurrence of different cloud types. Near the Gulf of Guinea in the southern part of WA, LLCs are prevalent all year round (Schrage and Fink, 2012; van der Linden et al., 2015; Adler et al., 2017; Danso et al., 2019). Farther north in the Sahelian region, these clouds are frequently observed during the WAM season from July to September (Bouniol et al., 2012). These LLCs consist of stratified clouds, most of which are nocturnal low stratus clouds covering wide areas and persisting into the early afternoon (Schuster et al., 2013; Babić et al., 2019a) as well as shallow convective clouds. LLCs composed of liquid water are well known to have a large impact on radiative transfer (Liou, 2002; Turner et al., 2007; Hill et al., 2018;). As a result, they drive the diurnal cycle of convection and the planetary boundary layer (Grabowski et al., 2006; Gounou et al., 2012). During the daytime, these clouds block a large portion of the incoming shortwave radiation reducing the irradiance at the earth's surface (Kniffka et al., 2019).

Several studies have been carried out in WA to understand LLCs, their variability, and the processes that aid in their formation, maintenance, and dissipation (e.g., Schrage and Fink, 2012; Schuster et al., 2013; Kalthoff et al., 2018; Dione et al., 2019; Lohou et al., 2020; Pedruzo-Bagazgoitia et al., 2020). The majority of those studies were carried out within the framework of two major field campaigns; the African Monsoon Multidisciplinary Analysis (AMMA) (Redelsperger et al., 2006) in 2006 and the Dynamics–Aerosol–Chemistry–Cloud Interactions in West Africa (DACCIWA) (Knippertz et al., 2015) in 2016. Both of these field campaigns provided an unprecedented database of surface-based observations of different cloud properties. Other studies on LLCs in the region have also been performed with satellite observations and model data (van der Linden et al., 2015; Adler et al., 2017; Hannak et al., 2017). These studies suggest that LLC formation is linked to a number of processes including but not limited to cooling caused by horizontal cold-air advection and the occurrence and strengthening of the nocturnal low-level jet (Schrage and Fink, 2012; Adler et al., 2017; Babić et al., 2019b).

Most of these studies, however, focused on night-time LLCs in the southern part of WA (e.g., Schrage and Fink, 2012; Schuster et al., 2013; Adler et al., 2017, 2019; Babić et al., 2019b). In the night, the nocturnal LLCs have no influence on the surface solar radiation due to the absence of sunlight. However, they persist long into the morning and early afternoon, thus directly influencing the amount of incoming solar irradiance and having a considerable impact on the energy balance of the earth surface as shown by Lohou et al. (2020). The conditions associated with these low clouds during the daytime in the region are less documented. As a result, our understanding of the impacts of these clouds on surface solar irradiance during the daytime is relatively limited. Moreover, most of the previous studies have been limited to the WAM season (e.g., Knippertz et al., 2011; Schuster et al., 2013; van der Linden et al., 2015; Dione et al., 2019). This is understandable as WA is cloudiest during the WAM season. However, it was shown that daytime LLCs exist in all seasons especially over southern WA (Danso et al., 2019). It is therefore important to understand the nature of such daytime LLCs over the whole region and not only during the WAM season. This is particularly challenging due to the lack of a long-term surface-based observational dataset in WA, thus limiting our understanding of these cloud systems. A few studies, which were done with simulations, reanalysis, and satellite data in the region (e.g., Knippertz et al., 2011; Schuster et al., 2013; van de Linden et al., 2015; Adler et al., 2017) have nevertheless shown results similar to those of ground observational studies (e.g., Adler et al., 2019; Babić et al., 2019b) to some extent.

In this general context, the main contribution of this study is to enhance our understanding of daytime LLCs in WA by focusing on daytime LLCs in both the dry and wet seasons with a state-of-the-art reanalysis dataset. Firstly, we will present the seasonal and diurnal distributions of the occurrence frequency of the daytime LLCs in two areas of WA with contrasting climate regimes (the Sahelian and the Guinean regions). We will then identify synoptic-scale conditions (specifically the moisture flux) associated with the presence of the daytime LLCs. Additionally, we will investigate the impact of LLC on surface heat fluxes and estimate the percentage of incoming surface shortwave (SW) radiation that is attenuated when these clouds are present.

This paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 describes the study area, datasets, and methodology. Section 3 presents the diurnal and monthly distribution of the occurrence of daytime LLCs, while the synoptic and local conditions associated with the occurrence of long-lasting LLCs are discussed in Sect. 4. Section 5 presents the estimated attenuation of incoming shortwave radiation during the occurrence of LLCs. Finally, conclusions are drawn in Sect. 6.

2.1 Data

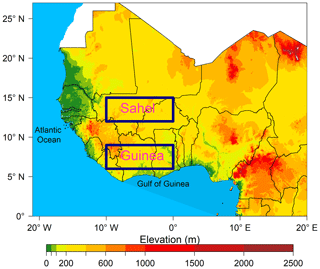

In this study, we analyze the fifth generation of the European Centre for Medium-range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Re-analysis, ERA51 (Hersbach et al., 2020), to understand the occurrence of LLCs and their associated synoptic conditions and land surface fluxes and to discuss their impacts on incoming shortwave radiation in WA (Fig. 1). The reanalysis is available at a temporal resolution of 1 h and has a native horizontal resolution of 0.25∘. However, due to more emphasis on large-scale conditions in this study, the data were directly extracted onto a regular grid from ECMWF. A period of 10 years from 2006 to 2015 was analyzed for the study. For this period a total of 43 800 data points consisting of only daytime hours from 06:00 to 17:00 LT, were thus considered.

Figure 1Map of West Africa showing the two selected windows (dark blue rectangles) used for identification of LLC events. The name denoted for each window is based on the climate zone of the window in the region.

ERA5 provides different variables of cloud cover properties. These cloud variables are produced in CY41R2 of the ECMWF's Integrated Forecasting System (IFS) and documented in Part IV of the IFS documentation (available at: https://www.ecmwf.int/en/elibrary/16648-part-iv-physical-processes, last access: 18 September 2019). The cloud cover variables consist of cloud fraction (CF) and cloud hydrometeors (liquid or ice water) and are available as 3D or 2D distributions. Here, we use the 3D distribution of cloud liquid and ice water content to show the atmospheric vertical profiles of clouds in selected areas over WA. The occurrence frequency of clouds may be defined by the hydrometeor content or the CF value. In this study, we determine the occurrence frequency based on the value of the 2D single-level CF, although, the liquid and ice water paths mostly determine the attenuation of incoming solar radiation in the atmosphere. The ERA5 CF depends on the subgrid-scale cloud scheme in the ECMWF IFS and can be non-zero when the cloud water content is zero (see Appendix A). The atmospheric conditions and radiative impacts are analyzed based on this occurrence. In this study, we focus on low clouds defined by ECMWF in the ERA5 product as all clouds integrated from the surface to 2 km altitude in the atmosphere (≈800 hPa). This includes all clouds with bases below 2 km.

Other ERA5 variables are analyzed to show some of the atmospheric and surface conditions during the occurrence of LLCs in order to understand the possible interactions between the surface and the lower atmosphere. These include specific humidity, zonal and meridional wind components, and the surface sensible and latent heat fluxes. Furthermore, we use the incoming downwelling shortwave radiation variable in ERA5 to estimate the percentage of incoming solar radiation that is attenuated in the presence of LLCs. We first performed a detailed evaluation of the ERA5 cloud fraction and radiation data with surface and satellite-based observations for some locations in WA. This evaluation revealed a reasonably good performance by ERA5 in reproducing the observations (see Supplement).

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Identification of LCC occurrence

Our analysis is based on the occurrence of LLCs in two sub-regional windows over WA (rectangular boxes in Fig. 1) denoted here as Guinea (6 to 9∘ N and 10∘ W to 0∘ E) and Sahel (12 to 15∘ N and 10∘ W to 0∘ E). These areas are chosen primarily due to their contrasting climate regimes (Gbobaniyi et al., 2014). The Guinea region, which includes countries like Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire, is currently undergoing significant economic and infrastructural developments, and thus the need for clean energy keeps increasing. Consequently, there are many ongoing solar energy projects in this region such as the 155 MW Nzema solar photovoltaic power project in Ghana (Kuwonu, 2016), which when completed will be the largest solar farm on the African continent. Côte d'Ivoire has planned to increase its share of variable renewable energy up to 11 % by the end of 2020 and up to 16 % by 2030. Thus, a 25 MW solar power plant is under construction in the northern part of the country in Korhogo while two solar power plant projects with a capacity of 30 MW each have been approved and will be built in the localities of Tuoba and Laboa in the northwestern part of the country (MPEER, 2019). Additionally, there are several planned and existing solar energy projects in the Sahel window, especially in Burkina Faso with the 33 MW capacity Zagtouli solar power plant (Moner-Girona et al., 2017), which is currently the largest solar energy project in the Sahelian part of WA.

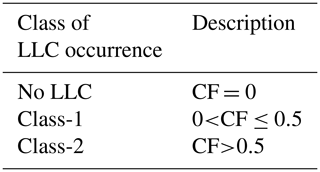

Occurrence or non-occurrence of LLC are first identified from the extracted data points based on the quantitative value of the CF in the two selected windows. This is used to show the diurnal and monthly distribution of the LLC occurrence. All timestamps with zero CF in the lower atmospheric level (up to 2 km) are designated as No LLC. Thus, hourly events of LLC occurrence are all timestamps with non-zero CF values including those with very small CF values. LLC events with very low CF values may show no or weak signals of the conditions that exist during their occurrence. Moreover, cloud radiative forcing is strongly dependent on the fractional coverage of clouds (Liu et al., 2011). Each LLC occurrence event is therefore classified as one of two classes depending on the CF value for that event. The definitions of the classes are provided in Table 1.

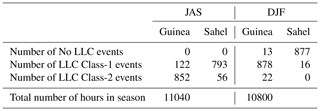

Table 2Number of events found for the occurrence of the three LLC classes in JAS and DJF. Composite analysis is performed based on these events for each class and season. For the study period, the total number of daytime hours are 11040 and 10800 in JAS and DJF, respectively.

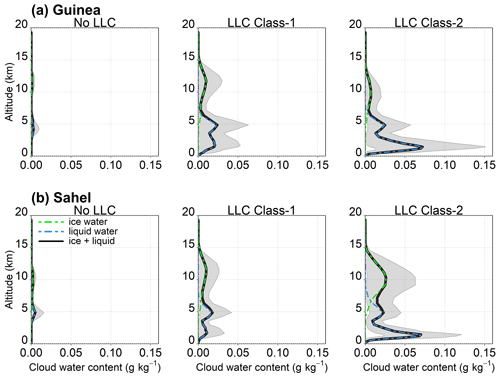

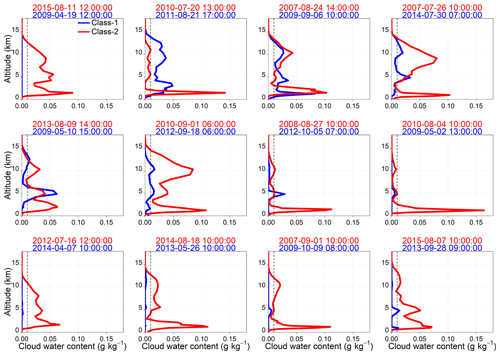

Though the focus of this study is on LLC occurrence and the definition of the different classes is based on the CF in the lower atmosphere only, the convoluted cloud climatology in WA with frequent multilayer clouds (Stein et al., 2011) may also mean that other clouds at higher altitudes may exist in addition to LLCs. Figure 2 illustrates this multilayer nature of clouds in WA in connection with LLC occurrence, by showing the mean (of all hourly events) vertical profile of cloud water content of each class in the two selected regions. For LLC Class-1 and Class-2 in both windows, the trimodal vertical distribution of tropical convection (Johnson et al., 1999) indicates the presence of higher-altitude clouds in addition to the LLCs. In the case of No LLC, high- and mid-level clouds could exist but with very low water content. This suggests and agrees with the satellite-based climatology of Stein et al. (2011) that LLCs frequently exist together with upper-level clouds in WA.

2.2.2 Identification of synoptic conditions during LLC occurrence

Recent studies (e.g., Adler et al., 2019; Babic et al., 2019b) have identified some physical processes relevant to the formation and maintenance of LLC in WA. They include but are not limited to the strengthening of the nocturnal low-level jet, horizontal cold-air advection, and background moisture level. Babic et al. (2019b) suggested the latter could play an important role in the formation of LLCs, but this has not received as much attention as the other processes. Based on the different classes defined in Table 1, the regional atmospheric circulation and moisture flux were analyzed for the 10-year period of this study. For that, a composite approach was used to produce robust results based on a large number of events. We only take into account the occurrence of the different LLC classes that last for a sufficiently long time for their associated mean atmospheric and surface conditions to be significant at the regional scale. Therefore, an event here refers to the occurrence of a given LLC class that lasts for at least 6 consecutive hours during the daytime. Composite analysis of the moisture flux (Qflux) and wind at 950 hPa was performed. Here, Qflux is defined as

where q is the specific humidity (in g kg−1), v is the meridional wind component (in m s−1), and N is the total number of events in a given LLC occurrence class. Since q is always positive, Qflux can either be negative or positive depending on the wind direction, with positive or negative values indicating northward and southward air movements, respectively. Over the sea, positive values of Qflux from the ocean toward the continent thus suggest that moisture is likely transported onto the land along with the wind.

Lohou et al. (2020) have shown that LLC occurrence also has a considerable impact on the surface heat fluxes in WA. Here, we examine the local surface sensible and latent heat fluxes in the selected windows to understand the daytime interaction of the land surface with the boundary layer and LLC occurrence. Due to the definition of LLCs used, the present study does not consider the impact of the atmospheric boundary layer (ABL) that may considerably modify the altitude of the low cloud. Indeed, ABL clouds have their bases higher than 2 km especially in the Sahel region during the dry season. In addition, some studies (Lohou et al., 2020; Pedruzo-Bagazgoitia et al., 2020; Zouzoua et al., 2020) have shown that some LLCs can be decoupled from the surface and are therefore not influenced by the surface heat fluxes. Therefore, having a higher cloud base threshold for LLCs may alter the analysis of the surface heat fluxes. The analysis was performed for two seasons representing two contrasting climate regimes associated with the southernmost position of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) over Guinea (in December, January, February (DJF)) and the northernmost position of the ITCZ over the Sahel (in July, August, September (JAS)).

2.2.3 Determination of cloud shortwave attenuation effects

To investigate the quantity of incoming downwelling shortwave radiation attenuated in the presence of LLCs (in W m−2) at a given time t, the cloud shortwave radiative effect (CRESW↓) was estimated by finding the difference between the downwelling shortwave radiation in all-sky conditions (SW↓) and the corresponding downwelling shortwave radiation in clear-sky conditions (). The which is directly available in ERA5, is a theoretical value computed at a given time based on the same atmospheric conditions (temperature, humidity, aerosols, etc.) as the SW↓ but assuming there are no clouds. To eliminate the influence of the wide range of daytime hours on its mean value, we expressed CRESW↓ as a percentage of the attenuated . Since SW↓ is usually lower than , the mean CRESW↓ over all events in a given LLC class will be negative. To avoid presenting a negative mean CRESW↓, the absolute of this value is used. Thus, the mean CRESW↓ of all events for a given LLC class is given by

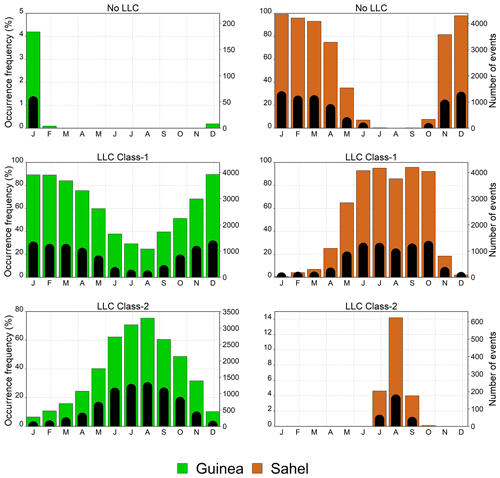

The monthly distribution of the occurrence frequency (hourly) of the three LLC classes is presented in Fig. 3 for the two selected regions (occurrences that last for at least 6 consecutive hours are in shown as black bars). In Guinea, events of No LLC are very rare (less than 200 in the 10-year data) and occur only in the DJF. On the other hand, LLCs occur in all months in this area. The occurrence of LLC events with lower fractional coverage (LLC Class-1) shows a clear seasonal cycle with the highest number of events in the dry and transitional seasons and the lowest number of events during June, July, August, and September (JJAS) which corresponds to the core of the monsoon season (Sultan et al., 2003). Coincidentally, LLC events with higher fractional coverage (LLC Class-2) occur most during the monsoon season. This period is associated with increased moisture influx from the Gulf of Guinea (Sultan and Janicot, 2003; Thorncroft et al., 2011) and cold-air advection which enhances low-cloud formation over the region during this period as shown by Adler et al. (2019) and Babic et al. (2019b). Interestingly, the peak of LLC Class-2 events occurs in August, the so-called “little dry season” in southern WA (Adejuwon and Odekunle, 2006; Chineke et al., 2010; Froidurot and Diedhiou, 2017). Whether this peak of LLC Class-2 events in August which coincides with reduced rainfall in southern WA is due to an increased occurrence of non-rain-bearing low clouds (and a decrease in rain-bearing ones) or not is beyond the scope of this paper but needs to be investigated in future.

Figure 3Monthly distribution of the occurrence frequency of hourly events for the three daytime LLC classes during the daytime in the Guinea (green bar) and Sahel (orange bar) regions defined in Fig. 1. The shorter black bars are the distribution of occurrences that last for at least 6 consecutive hours (the actual value has been multiplied by a factor of 4 to improve the legibility of the distribution).

In the Sahel, events of No LLC are rather frequent (unlike Guinea) and occur in every month except in August when the monsoon is fully developed over the Sahelian region of WA (Sultan et al., 2003; Thorncroft et al., 2011). Similarly, LLC Class-1 events are frequent throughout the year but with the highest occurrences from July to October (with a slight decrease in August) and lowest occurrences during the dry season. LLC Class-2 events are marked with a strong seasonal signature, occurring only from July to October with a distinct peak occurrence in August when the ITCZ is at its northernmost latitude over WA (Sultan and Janicot, 2000; Nicholson, 2009, 2018). This period also coincides with the maximum rainfall over the Sahelian region (Nicholson, 2013) and suggests a strong link between the occurrence of LLC Class-2 events and the Sahelian rainfall. This is an indication that LLC Class-2 in the Sahel is likely related to rainfall events in the region. Again, Mathon et al. (2002b) showed that cloud cover associated with a sub-population of mesoscale convective systems (MCSs) in the Sahel is modulated at the synoptic-scale during the African easterly wave activity, with an increase in the cloud cover in and ahead of the trough and maximum rainfall behind the wave trough.

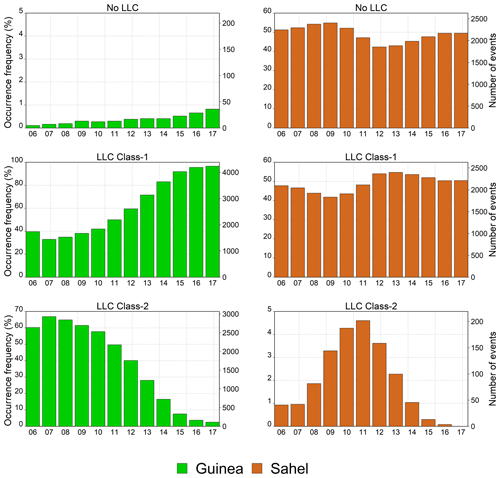

The daytime distribution of occurrence frequency of the three LLC classes is presented in Fig. 4 for the two selected areas. The distribution presents the total occurrence frequency of all seasons combined. In Guinea, the occurrence frequency of No LLC events does not present a very well-marked diurnal cycle with a slightly higher number of events occurring at 17:00 UTC, though these events are extremely rare (less than 25 for the 10 years). In contrast, both LCC Class-1 and Class-2 occurrences present well-defined diurnal cycles. The occurrence of LLC Class-1 events is low during the early morning (lowest at 07:00 UTC) and increases progressively throughout the day to late in the afternoon. By contrast, LLC Class-2 events are high early in the morning (highest at 07:00 UTC) but decrease continuously over the course of the day to the late afternoon (17:00 UTC). The early morning peak in the LLC Class-2 events could be as a result of the contribution of residuals from nocturnal low-level stratus clouds which persist long into the day (Kalthoff et al., 2018). These clouds usually have large fractional coverage during their occurrence in the night (van der Linden et al., 2015) but start to dissipate during the daytime (Kalthoff et al., 2018). The continuous decreasing and increasing in the event number of LLC Class-2 and LLC Class-1, respectively, from morning to late afternoon could, therefore, be linked to the gradual dissipation of those nocturnal low-level stratus clouds during the day. Additionally, the early morning peak in the events of LLC Class-2 could also be partly linked to contributions from tropical oceanic low-level convection, which is maximal during the early morning (Yang and Slingo, 2001). The proximity of the Guinean region to the ocean means that cold air over the Gulf of Guinea could be advected inland which will, in turn, enhance LLC formation.

Figure 4Diurnal distribution of occurrence frequency of the three daytime LLC classes during the daytime in the Guinea and Sahel regions as defined in Fig. 1. All seasons are included in the distribution shown.

In the Sahel region, events of No LLC occur without a well-marked diurnal cycle but are slightly lower around midday. Similarly, LLC Class-1 events do not present a very distinct diurnal cycle. On the other hand, events of LLC Class-2 show a clear and well-marked diurnal cycle with a higher occurrence frequency in the late morning to midday (highest at 11:00 UTC) and lower values during early mornings and late afternoon. This tendency seems to be strongly controlled by surface processes such as continental daytime solar heating (Mallet et al., 2009). Moreover, it could further be related to the occurrence of deep MCSs whose convective parts will be regarded as low clouds if found within the lowest 2 km of the atmosphere. These MCSs present a fairly similar evolution (both seasonally (Fig. 3) and diurnally) as the LLC Class-2 in this region of WA (Vizy and Cook, 2019). Therefore, there is a higher likelihood of an MCS in the LLC Class-2 events than Class-1, and it is reasonable to assume that most of the LLC Class-2 events in the Sahel are the well-documented deep MCSs (Fig. A1 in Appendix A) that are responsible for around 90 % of total rainfall in the region (Mathon et al., 2002a; Goyens et al., 2012; Vizy and Cook, 2019).

The synoptic conditions associated with the occurrence of the different LLC classes are mainly presented for the JAS and DJF seasons. The total number of daytime hours in JAS and DJF during the 10 years are 11 040 and 10 800, respectively. Only occurrences that last for at least 6 consecutive hours are considered in order to analyze these conditions (i.e., here, an event refers to an occurrence that persists for at least 6 consecutive hours). Table 2 presents the number of the “6 consecutive hours” events extracted for each class and for both seasons over the 10 years. During the JAS season, no occurrence of No LLC events was detected in both the Guinea and Sahel window (i.e., daytime LLCs are always present in both regions during the JAS). LLC Class-1 events dominated the Sahel region during JAS (with 793 events), but, by contrast, LLC Class-2 events dominated the Guinea region (with 852 events). In DJF, No LLC events dominated the Sahel (with 877 events) and no LLC Class-2 occurrence has been identified in this area during this season. In Guinea, on the other hand, LLC Class-1 occurrences dominated the area during DJF (with 878 events). Composites of the different variables are thus analyzed and then discussed only based on the extracted events for each class and each season, as presented in Table 2.

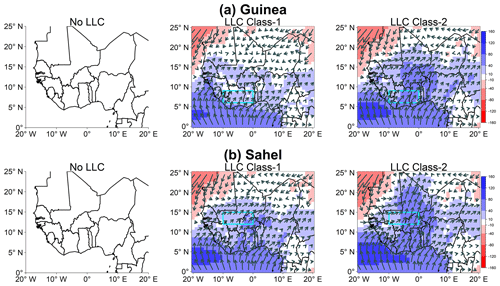

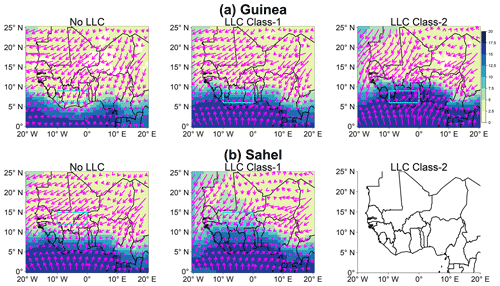

4.1 Atmospheric circulation and moisture flux

The occurrence of daytime LLC events in the selected windows is related to large-scale dynamics of the atmosphere over the WA region. Figures 5 and 6 present the composites of Qflux and the atmospheric circulation at 950 hPa for JAS and DJF, respectively, and for the two studied regions. During JAS in both regions (Fig. 5), the occurrence of LLC Class-1 and Class-2 events is related to high moisture flux dominated by strong southwesterly winds (positive Qflux) from the Guinean Gulf. The moisture flux is stronger during the occurrence of LLC Class-2 events than LLC Class-1 events. This is true for LLC occurrence in both regions; however, the moisture flux is more intense for LLC occurrence in the Sahel in terms of its inland penetration. There are no events of No LLC in either the Sahel or Guinea during JAS. During DJF in both regions (Fig. 6), events with No LLC are characterized by dry northeasterly winds that inhibit LLC formation. The occurrence of LLC Class-1 events in Guinea and the Sahel is characterized by southerly winds just at the southern coast but does not penetrate the area of the two windows. Nevertheless, both LLC Class-1 and Class-2 events are associated with significant specific humidity (true for both seasons) unlike No LLC events with very low specific humidity (see Fig. B1 in Appendix B). This is in agreement with Babic et al. (2019b), who found that the most distinct difference between LLC and No LLC events is in the specific humidity, suggesting that the background moisture may play a crucial role in the formation and maintenance of low clouds in WA. Additionally, the LLC Class-1 events during DJF (in the Sahel) are related to positive anomalies of specific humidity that seem to have been transported onto the continent from the North Atlantic (not shown). LLC Class-2 events in Guinea are associated with a much stronger moisture flux in the region (Fig. 6) as well as a positive anomaly of specific humidity within and around the window (not shown).

Figure 5Composites of 950 hPa moisture flux (colors, g kg−1 m s−1) and wind (vectors, m s−1) over WA for the three LLC occurrence classes in the Guinea (a) and Sahel (b) windows during JAS from 2006 to 2015. Only occurrences that last for at least 6 consecutive hours are considered. Wind vectors are averaged over two grid points in both the x and y directions. No event of the No LLC class has been extracted in the Guinea and Sahel regions during JAS, hence the empty plots.

Figure 6Same as Fig. 5 but for DJF. No event of LLC Class-2 has been extracted in the Sahel area during DJF, hence the empty plot.

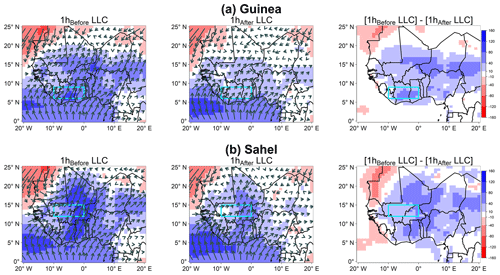

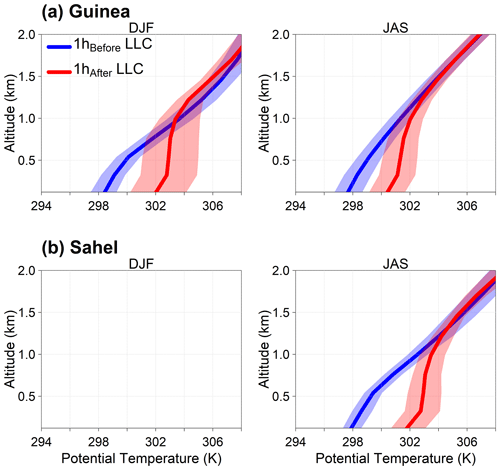

The moisture fluxes presented so far are those present when LLC events are identified. However, it is also interesting to investigate the moisture flux before and after the LLC occurrence in order to analyze their contribution to the maintenance or triggering of these systems. To do this, we analyze the composite moisture flux (at 950 hPa) of the first hour just before the LLC event (1 hBefore LLC) and the first hour just after the LLC disappears (1 hAfter LLC) and the difference between the two periods. This is illustrated for LLC Class-2 during the JAS season in both Guinea and the Sahel (Fig. 7). In both regions, the moisture flux during 1 hBefore LLC is larger than 1 hAfter LLC and there is a significant difference between the two periods as shown in Fig. 7. This is also true for the composites of specific humidity only (not shown). During 1 hBefore LLC, the water vapor associated with the moisture flux is likely cooled by some cold-air advection into the region, which leads to saturation and, consequently, LLC formation. Indeed, the vertical profile of the potential temperature in the lower atmosphere during the two periods shows a strong temperature decrease just before the LLC occurrence and an increase after its disappearance (Fig. B2 in Appendix B). This result, which is in agreement with the finding of Babic et al. (2019b), may be an indication of the cooling caused by the cold-air advection. Over the Guinea region, studies have shown that cooling by the horizontal advection of cold air from the Gulf of Guinea contributes significantly to the formation of LLC (e.g., Adler et al., 2019; Babic et al., 2019b). In the Sahel region, moist air advection may be crucial for LLC formation as suggested by Parker et al. (2005) and Monerie et al. (2020). However, before LLC formation in the Sahel region, there may also be some cooling due to meridional advection (Marsham et al., 2013) as well as cold-air advection from the North Atlantic, which could explain the strong temperature reduction during 1 hBefore LLC (Fig. B2).

Figure 7Composites of 950 hPa moisture flux (colors, g kg−1 m s−1) and wind (vectors, m s−1) over WA for the hour preceding LLC Class-2 occurrence (1 hBeforeLLC) and after it disappears (1 hAfterLLC) and the difference between the two periods during JAS from 2006 to 2015. Wind vectors are averaged over two grid points in both the x and y directions.

4.2 Surface heat fluxes

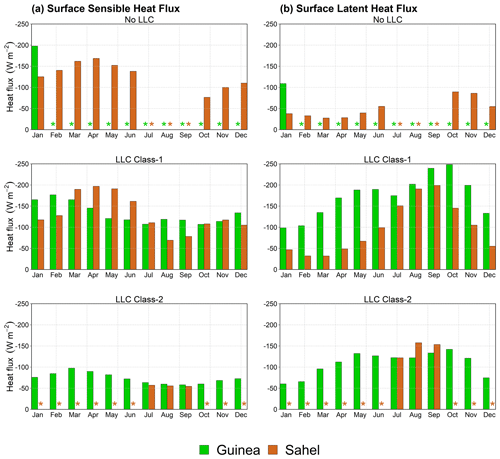

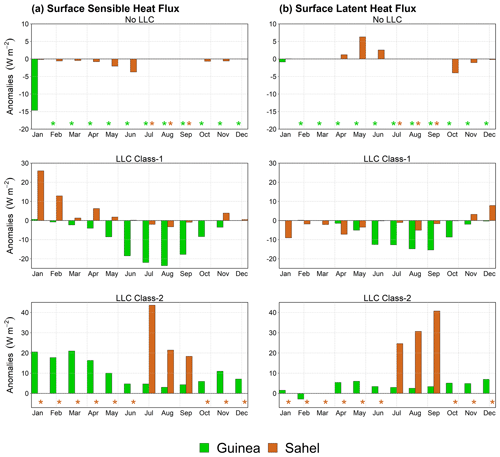

Figures 8 and 9, respectively, present the monthly mean and anomalies of the surface heat fluxes, computed over the two selected regions for the three LLC occurrence classes. For a particular hour i, on a given day and month during the 10 years, the heat flux anomaly is the difference between the actual heat flux value and the 10-year mean. For example, the heat flux anomaly at 12:00 UTC on 1 January 2006 was determined by taking the difference between the actual heat flux at 12:00 UTC on 1 January 2006 (HFi) and the 10-year mean of all heat flux values at 12:00 UTC on 1 January (); i.e.,

where HFanom_i is the heat flux anomaly. The mean monthly anomaly is then computed by finding the mean of hourly anomalies in the month. The ECMWF convention for vertical fluxes including the sensible and latent heat fluxes is positive downwards and negative upwards.

Figure 8Monthly mean (a) surface sensible heat and (b) surface latent heat fluxes computed in the Guinea and Sahel regions during the occurrence of the three LLC classes from 2006 to 2015. The orange and green stars mean that there was no occurrence of the particular LLC class events in the region during that month; hence the composites were not computed. Only occurrences that last for at least 6 consecutive hours are considered.

Figure 9Monthly mean anomalies of (a) surface sensible heat and (b) surface latent heat fluxes computed in the Guinea and Sahel regions for the occurrence of the three LLC classes from 2006 to 2015. The orange and green stars mean that there was no occurrence of the particular LLC class events in the region during that month; hence the composites were not computed. Only occurrences that last for at least 6 consecutive hours are considered.

No LLC events occur almost throughout the entire year in the Sahel (except JAS) and only during January in the Guinean region. In both areas, the occurrence of these events leads to high negative sensible heating (Fig. 8) indicating an upward transfer of sensible heat. Indeed, during No LLC events, much of the incoming radiation heats the surface, making it warmer than the air directly above it, leading to an upward sensible heat flux. Both regions are characterized by negative anomalies of sensible heat (Fig. 9) suggesting a much stronger than usual upward transfer of sensible heat. The mean latent heat fluxes during No LLC events are also negative but significantly lower than the sensible heat (Fig. 8). Thus, most of the energy from the surface is used to heat the atmosphere rather than evaporating moisture. This could be as a result of a low moisture gradient between the soil and the air during those events especially in the dry season when both soil and air moisture are extremely low in the region. The lack of moisture in the region inhibits the formation of LLC during these events. In the Sahel region, there are positive anomalies of latent heat (from April to June), which indicates a downward transfer of energy from the atmosphere to the surface.

During LLC occurrence, a portion of the incoming SW radiation is blocked. Therefore, the warming of the surface is reduced during LLC occurrence in both regions. However, due to the higher cloud fraction during LLC Class-2 events, a larger quantity of the downwelling shortwave radiation is blocked. Consequently, the associated surface warming is much lower during LLC Class-2 than the Class-1 events (lower negative sensible heat fluxes than Class-1 events in Fig. 8a). This result suggests that the LLC Class-2 events are most likely the low stratiform clouds which are known to cover large portions of the sky or the deep convective clouds which extend to the upper levels of the atmosphere, generating anvils in the process. With regards to the former, Lohou et al. (2020) have shown that these low stratiform clouds have significant impacts on the energy balance of the earth's surface during the daytime in the Guinea region. The latter have also been shown to have large impacts on the incoming shortwave radiation, especially in the Sahel region during the monsoon season (Bouniol et al., 2012).

In terms of anomalies, the LLC Class-2 events present positive values (Fig. 9a) over both regions suggesting a net downward transfer of sensible heat. This could be due to two main reasons. Firstly, a larger portion of the sky is blocked during these events leading to lower sensible heating at the surface. Additionally, large amounts of energy are released in the lower atmosphere during the formation of these clouds, which in turn leads to a higher sensible heat flux in the atmosphere than when there are no LLCs or when the cloud fraction is low. On the other hand, LLC Class-1 in the Guinean region presents negative anomalies of sensible heat that suggest a net upward transfer of sensible heat during these events. As these LLCs do not cover a large portion of the sky, a large amount of shortwave radiation still warms the surface. Moreover, the energy released in the atmosphere is not as much as for LLC Class-2 events. Thus, during these events, the atmosphere has a relatively lower sensible heat flux. It is rather surprising that the Sahel region presents positive anomalies (except in JAS) for sensible heat. As suggested by Bouniol et al., (2012), such a result should not be interpreted exclusively in terms of the radiative effects of clouds but rather in terms of the coupled interactions between fluctuations in temperature, water vapor, and clouds in this region. However, this is beyond the scope of the present study.

During LLC occurrence, the large mean negative latent heat values indicate more evaporation from the surface (Fig. 8b). Interestingly, the transfer of latent heat upwards is higher in Class 1 than in Class 2. Since only a small portion of the sky is covered during LLC Class-1 events, the surface still receives a significant amount of downwelling shortwave radiation. Therefore, the surface continues to be warmed better by the sun's radiation during LLC Class-1 events than Class-2 events. As a result, the evaporation of moisture at the surface is much higher during the occurrence of the former. There are negative anomalies of the surface latent heat (Fig. 9b) in both regions during LLC Class-1 events in all months (except in November and December in the Sahel). This signifies a more intense upward transfer of latent energy from evaporation during these events. On the other hand, LLC Class-2 events are associated with positive anomalies of latent heat. This is likely due to two main reasons. Firstly, the reduced incoming downwelling shortwave radiation decreases evaporation at the surface. Secondly, large amounts of latent heat of condensation are released in the atmosphere during the formation of the clouds. There is therefore a greater amount of latent energy in the atmosphere than at the surface and a net downward transfer of this energy.

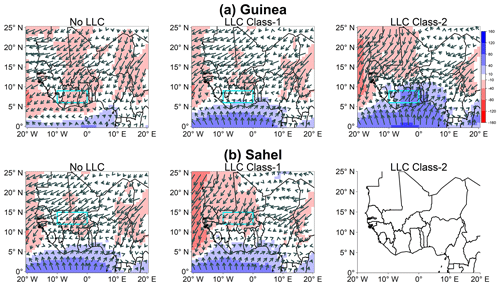

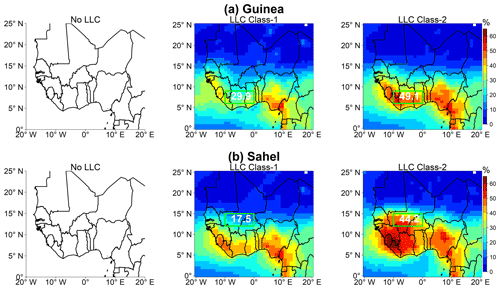

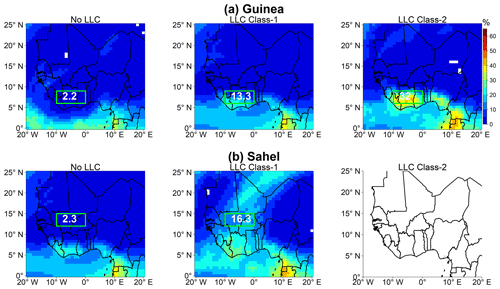

In Figures 10 and 11, the regional distribution of cloud radiative effect on incoming downwelling shortwave radiation during JAS and DJF is presented, respectively, as the percentage of incoming shortwave radiation attenuated during the occurrence of LLCs in the two regions as computed with Eq. (3) (CRESW↓). In this section, we will focus more on the mean CRESW↓ in each of the regions. Firstly, there is a strong seasonal variability of CRESW↓ over the entire WA region. It is obvious that shortwave attenuation is much higher during JAS than during DJF over the entire region as a result of increased cloud coverage during the monsoon season (Bouniol et al., 2012; Danso et al., 2019). This is true whether LLCs are present or not. During the occurrence of LLCs, the values of CRESW↓ are much lower for LLC Class-1 than LLC Class-2 events, whatever the region and the season. This clearly shows the strong dependence of CRESW↓ on the fractional coverage of clouds as previously discussed by Liu et al. (2011).

Figure 10Mean attenuation of incoming downwelling shortwave radiation (%) during JAS from 2006 to 2015 over WA for the occurrence of the three LLC classes in the Guinea (a) and Sahel (b) regions. Only occurrences that last for at least 6 consecutive hours are considered. Numbers in the box refer to the mean percentage attenuation of incoming shortwave radiation in that specific area. No event of the No LLC class has been extracted in the Guinea and Sahel regions during JAS, hence the empty plots.

Figure 11Same as Fig. 10 but for DJF. No event of LLC Class-2 has been extracted in the Sahel region during DJF, hence the empty plot.

In JAS, the strong impacts of LLCs on incoming shortwave radiation are seen from the high CRESW↓ values during LLC occurrence. During the occurrence of LLC Class-1 events, the mean percentage attenuation of incoming shortwave radiation becomes 29.9 % and 17.5 %, respectively, in the Guinean and Sahelian regions. In the same way, 49.1 % and 44.2 % of incoming shortwave radiation is attenuated on average in Guinea and the Sahel, respectively, during events of LLC Class-2. Though these values are attenuated in the two regions under consideration, higher losses can be experienced in different areas over the region during those events. For instance, during LLC Class-2 events in the Sahel, the areas around the southern coast and the Guinea highlands experience much higher CRESW↓ values (up to 65 %). This could be due to the presence of more clouds in those areas which extend into the Sahel region.

During DJF, during events of No LLC in Guinea and the Sahel, about 2.2 % and 2.3 % (Fig. 11) of the incoming shortwave radiation is lost on average, respectively. Even though there is no LLC occurrence during these events, this attenuation value is due to the possible presence of other cloud types at the upper levels. However, similar to the JAS season, the occurrence of LLCs leads to higher CRESW↓ in both regions. In Guinea, 13.3 % of incoming shortwave radiation is lost on average during the occurrence of LLC Class-1 events, while 32 % is lost during LLC Class-2 events. In the Sahel, the mean attenuation during the occurrence of LLC Class-1 events is 16.3 %.

The large attenuation of incoming shortwave radiation during LLC occurrence (especially LLC Class-2) could be detrimental to planned solar energy application projects if not properly planned. For instance, during the JAS season in the Guinea region (and southern part of WA in general), the dominance of LLC Class-2 events (Table 2 and Fig. 3) means that surface solar radiation will be significantly reduced for a large number of periods. Although there are equally high losses of incoming solar radiation in the Sahel during LLC Class-2 events in JAS, these events are much lower than in the Guinea region. Besides, the Sahel region has several persistent periods with no LLCs compared to the Guinea region in the other months of the year, especially during DJF. However, other issues that are not discussed in this paper such as dust (e.g., Bonkaney et al., 2017) could severely hinder solar energy projects in the Sahel region. In all cases, the implementation of large-scale solar energy projects in both regions requires meticulous planning to ensure that the intense cloudiness over the region and the high variability of these clouds as shown by Danso et al. (2019) do not compromise the long-term aims of those developments.

In this paper, we made use of the state-of-the-art hourly reanalysis dataset from ECMWF-ERA5 from 2006 to 2015 to analyze the occurrence of daytime LLCs in WA. The analysis was performed for both the wet (JAS) and dry (DJF) seasons and focused on two climatically contrasting areas in the region (i.e., Guinea and the Sahel). We have first identified events of LLC occurrence in both regions. We then analyzed some regional- and local-scale environmental conditions which occur during those events of LLC occurrence. This analysis mainly focused on the moisture flux before, during and after the LLC occurrence. We also analyzed the impacts of the LLC occurrence of on the surface heat fluxes. Finally, the attenuation of incoming shortwave radiation during the occurrence of LLC in the region was estimated. To account for the influence of fractional coverage of LLC on the attenuation of incoming shortwave radiation, we classified the events of LLC occurrence into two groups: events with low fractional coverage (LLC Class-1) and events with high fractional coverage (LLC Class-2). The main findings of the study are summarized below.

The occurrence frequency of daytime LLCs is characterized by significant diurnal and seasonal variations. (i) Over Guinea, the occurrence of LLC Class-1 events is lower during the core of the monsoon season (JJAS), while LLC Class-2 events are much higher during this period. During the day, LLC Class-2 events occur frequently during the early morning, while LLC Class-1 is rather frequent during the late afternoon. (ii) Over the Sahel, the occurrence of both LLC Class-1 and LLC Class-2 events is higher during the core of the monsoon season. Occurrence frequency of LLC Class-2 events is higher around midday, while for LLC Class-1 events, it does not show a strong diurnal variation.

During JAS, the occurrence of LLCs (both Class-1 and Class-2) in both Guinea and the Sahel is associated with high moisture flux dominated by significant background moisture and strong southwesterly winds from the Gulf of Guinea. We also found that just before the occurrence of LLC, the temperature in the lower atmosphere is significantly reduced (Appendix B). This is due to cold-air advection which leads to saturation as shown in previous studies (e.g., Adler et al., 2019, and Babic et al., 2019a).

In the dry season, the moisture flux is not as intense as in JAS but the background moisture content is significant during the occurrence of LLCs. The region is dominated by dry northeasterly winds during this period. Other processes such as the atmospheric waves and jets in the region (African easterly wave, African easterly jet, etc.) may also contribute to the occurrence of LLCs, but these are not analyzed in this study. These processes are, however, only relevant in the wet season.

The occurrence of LLCs has significant impacts on surface heat fluxes. LLC Class-2 events lead to a significant reduction in the transfer of energy (both sensible and latent) upward and a significant release of energy in the atmosphere, which causes a net downward transfer of energy.

Attenuation of incoming shortwave radiation is higher during JAS than DJF and depends on the fractional coverage of LLCs. In JAS, the occurrence of LLC Class-1 leads to mean attenuations of 29.9 % and 17.5 %, respectively, in Guinea and the Sahel. LLC Class-2 leads to mean attenuations of 49.1 % and 44.2 % in Guinea and the Sahel, respectively. In DJF, mean attenuations of 13.3 % and 32 % are experienced in Guinea for LLC Class-1 and Class-2 events, respectively. In the Sahel, the occurrence of LLC Class-1 events leads to a 16.3 % attenuation of incoming shortwave radiation. It should however be noted that ERA5 slightly overestimates cloud fraction in the lower atmosphere over WA (see Supplement).

By using the ERA5 cloud cover dataset in this study, we have provided important information on daytime LLCs in WA – a region notably known for its lack of surface observations. Previous studies have mostly focused on nighttime LLCs in the southern part of WA and only during the WAM season. Here, we expanded to the Sahel region and investigated the occurrence of LLCs during the dry season as well. The study helps to identify some conditions such as the background moisture level, which is known to contribute to LLC formation in the region. Again, this study also helps to provide an idea of the impacts of these clouds on the surface energy budget especially on the attenuation of incoming shortwave radiation during LLC occurrence. The results of the seasonal and diurnal distributions of LLCs as well as of that regarding the attenuation of incoming shortwave radiation during LLC occurrence could be useful when making feasibility studies for large-scale solar energy projects.

The occurrence frequency of clouds may be defined based on the value of the cloud water content (liquid and ice) or the cloud fraction (CF). In this study, we defined the occurrence frequency of low-level clouds (LLCs) based on the value of CF. LLC occurrence was first classified as Class-1 (0< CF ≤ 0.5) or Class-2 (CF >0.5). In ERA5, CF can be larger than zero for zero liquid or ice water content. This is illustrated in Fig. A1, which shows the vertical profiles of cloud water content during the occurrence of random LLC Class-1 and Class-2 events. It can be seen in some of the profiles (for Class-1) that the liquid and ice water content in the lowest 2 km is zero (but these events have CF >0 in the lowest 2 km in the profile).

Figure A1Vertical profiles of cloud hydrometeor content (liquid and ice water) during the occurrence of LLC Class-1 and Class-2 events in the Sahel region. These events are randomly chosen. The timestamps at the top of each plot are the times for those LLC events. The black dashed vertical line shows the threshold for deep convective clouds as defined by Storer and Van den Heever (2013).

Figure A1 is also used to suggest the kind of cloud types that may be dominant in each class. In this case, we say that, in the Sahel region, there is a higher probability of getting a mesoscale convective system (MCS) in LLC Class-2 than Class-1. Figure A1 is the vertical profile of 12 random events of LLC Class-1 and Class-2 in the Sahel region. Based on the work of Storer and Van den Heever (2013), we designate an event as a “MCS event'; when there is a column containing at least 0.01 g kg−1 cloud water (black dashed vertical line in Fig. A1) through a continuous depth of 8 km. From the 12 random profiles in Fig. A1, there are at least 7 LLC Class-2 events (and just one for LLC Class-1) that satisfy this MCS definition. The number of LLC Class-2 events is extremely low compared to LLC Class-1 (see Fig. 3); therefore, the likelihood that an event will be an MCS is relatively higher in the LLC Class-2 events.

Figure B1 shows the composites of specific humidity (colors) and winds (vectors) during the occurrence of the different LLC occurrence classes in both Guinea and the Sahel for the DJF season. During No LLC events, the moisture content in the region of the two windows is very low or zero. However, during LLC occurrence, the moisture content in the region is significant. This indicates that the background moisture plays an important role in the occurrence of these clouds. This result is confirmed in the recent study of Babic et al. (2019b), who found that in southern WA, the most distinct difference between LLC and No LLC events is in the specific humidity.

Figure B2 presents the composite vertical profile of the potential temperature for the hour before (1 hBefore LLC) and after (1 hAfter LLC) the occurrence of LLC Class-2 in both regions for DJF and JAS.

Figure B1Composites of 950 hPa specific humidity (colors, g kg−1) and wind (vectors, m s−1) over WA for the three LLC occurrence classes in the Guinea (a) and Sahel (b) windows during DJF from 2006 to 2015. Only occurrences that last for at least 6 consecutive hours are considered. Wind vectors are averaged over two grid points in both the x and y directions. No event of LLC Class-2 has been extracted in the Sahel area during DJF, hence the empty plot.

The profile is shown for the lowest 2 km of the atmosphere. There is no LLC Class-2 event in the Sahel during DJF, hence the empty plot. The profiles presented here suggest that before the LLC occurrence, there is a significant temperature decrease in the lower atmosphere. In the Guinea region, this is likely due to the well-documented horizontal cold-air advection from the Gulf of Guinea (Adler et al., 2019; Babic et al., 2019b), which leads to the saturation of water vapor and consequent formation of LLCs. There could also be some cold-air advection in the Sahel region, as suggested by Marsham et al. (2013). The temperature sharply increases after the disappearance of the LLC, and this could be due to enhanced surface warming from incoming shortwave radiation (since attenuation of the incoming radiation is less in cloudless conditions).

Figure B2Vertical profile of the mean potential temperature (solid line) for the lowest 2 km of the atmosphere, computed in Guinea and the Sahel for all the “1 h” preceding LLC Class-2 occurrence and all the “1 h” after its disappearance. The shaded regions represent the 10th and 90th inter-percentile range. No event of LLC Class-2 has been extracted in the Sahel area during DJF, hence the empty plot.

We are grateful to the institutions that provided the data used in this work: ERA5 data are publicly provided by the Copernicus Climate Data Store (CDS), https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/home (last access: 18 September 2019; Hersbach et al., 2018); the 2B-GEOPROF-LIDAR data product is provided by the CloudSat Data Processing Center, http://www.cloudsat.cira.colostate.edu/data-products/level-2b/2b-geoprof-lidar (last access: 18 August 2020; Mace and Zhang, 2014); surface measurements of shortwave radiation are provided by the AMMA-CATCH Database (Galle et al., 2018) and can be accessed on request to the managers of the AMMA-CATCH Database.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-11-1133-2020-supplement.

DKD, SA, and AD determined the analysis framework. DKD carried out all calculations, produced the figures, and wrote the first draft. KK and ATK contributed to the interpretation of the figures. All authors contributed to the analyses and to the editing of the first draft.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We are grateful to the Institute of Environmental Geosciences (IGE; University of Grenoble – Alpes, France) and to Laboratoire de Physique de l'Atmosphère et de Mécanique des Fluides (LAPA-MF; University Felix Houphouet Boigny, Côte d'Ivoire), who hosted DKD during his stay in Grenoble and Abidjan in the framework of the International joint laboratory NEXUS on climate, water, land, energy and climate services (LMI NEXUS).

This research has been supported by the France National Research Institute for Sustainable Development IRD (Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, France).

This paper was edited by Gabriele Messori and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Adejuwon, J. O. and Odekunle, T. O.: Variability and the severity of the “Little Dry Season” in southwestern Nigeria, J. Climate, 19, 483–493, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI3642.1, 2006.

Adler, B., Kalthoff, N., and Gantner, L.: Nocturnal low-level clouds over southern West Africa analysed using high-resolution simulations, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 899–910, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-899-2017, 2017.

Adler, B., Babić, K., Kalthoff, N., Lohou, F., Lothon, M., Dione, C., Pedruzo-Bagazgoitia, X., and Andersen, H.: Nocturnal low-level clouds in the atmospheric boundary layer over southern West Africa: an observation-based analysis of conditions and processes, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 663–681, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-663-2019, 2019.

Armstrong, S. and Hurley, W. G.: A new methodology to optimise solar energy extraction under cloudy conditions, Renew. Energy, 35, 780–787, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2009.10.018, 2010.

Babić, K., Adler, B., Kalthoff, N., Andersen, H., Dione, C., Lohou, F., Lothon, M., and Pedruzo-Bagazgoitia, X.: The observed diurnal cycle of low-level stratus clouds over southern West Africa: a case study, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 1281–1299, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-1281-2019, 2019a.

Babić, K., Kalthoff, N., Adler, B., Quinting, J. F., Lohou, F., Dione, C., and Lothon, M.: What controls the formation of nocturnal low-level stratus clouds over southern West Africa during the monsoon season?, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 13489–13506, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-13489-2019, 2019b.

Bonkaney, A., Madougou, S., and Adamou, R.: Impacts of Cloud Cover and Dust on the Performance of Photovoltaic Module in Niamey, J. Renew. Energy, 2017, 9107502, https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9107502, 2017.

Bouniol, D., Couvreux, F., Kamsu-Tamo, P. H., Leplay, M., Guichard, F., Favot, F., and O'connor, E. J.: Diurnal and seasonal cycles of cloud occurrences, types, and radiative impact over West Africa, J. Appl. Meteorol. Clim., 51, 534–553, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAMC-D-11-051.1, 2012.

Chineke, T. C., Jagtap, S. S., and Nwofor, O.: West African monsoon: Is the August break “breaking” in the eastern humid zone of Southern Nigeria?, Clim. Change, 103, 555–570, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-009-9780-2, 2010.

Christensen, J. H., Kumar, K. K., Aldrian, E., An, S.-I., Cavalcanti, I. F. A., Castro, M. de, Dong, W., Goswami, P., Hall, A., Kanyanga, J. K., Kitoh, A., Kossin, J., Lau, N.-C., Renwick, J., Stephenson, D. B., Xie, S.-P., and Zhou, T.: Climate phenomena and their relevance for future regional climate change, in: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Stocker, T. F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M., Allen, S. K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., and Midgley, P. M., 1217–1308, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2013.

Danso, D. K., Anquetin, S., Diedhiou, A., Lavaysse, C., Kobea, A., and Touré, N. E.: Spatio-temporal variability of cloud cover types in West Africa with satellite-based and reanalysis data, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 145, 3715–3731, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3651, 2019.

Dione, C., Lohou, F., Lothon, M., Adler, B., Babić, K., Kalthoff, N., Pedruzo-Bagazgoitia, X., Bezombes, Y., and Gabella, O.: Low-level stratiform clouds and dynamical features observed within the southern West African monsoon, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 8979–8997, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-8979-2019, 2019.

Froidurot, S. and Diedhiou, A.: Characteristics of wet and dry spells in the West African monsoon system, Atmos. Sci. Lett., 18, 125–131, https://doi.org/10.1002/asl.734, 2017.

Galle, S., Grippa, M., Peugeot, C., Moussa, I. B., Cappelaere, B., Demarty, J., Mougin, E., Panthou, G., Adjomayi, P., Agbossou, E. K., Ba, A., Boucher, M., Cohard, J.-M., Descloitres, M., Descroix, L., Diawara, M., Dossou, M., Favreau, G., Gangneron, F., Gosset, M., Hector, B., Hiernaux, P., Issoufou, B.-A., Kergoat, L., Lawin, E., Lebel, T., Legchenko, A., Abdou, M. M., Malam-Issa, O., Mamadou, O., Nazoumou, Y., Pellarin, T., Quantin, G., Sambou, B., Seghieri, J., Séguis, L., Vandervaere, J.-P., Vischel, T., Vouillamoz, J.-M., Zannou, A., Afouda, S., Alhassane, A., Arjounin, M., Barral, H., Biron, R., Cazenave, F., Chaffard, V., Chazarin, J.-P., Guyard, H., Koné, A., Mainassara, I., Mamane, A., Oi, M., Ouani, T., Soumaguel, N., Wubda, M., Ago, E. E., Alle, I. C., Allies, A., Arpin-Pont, F., Awessou, B., Cassé, C., Charvet, G., Dardel, C., Depeyre, A., Diallo, F. B., Do, T., Fatras, C., Frappart, F., Gal, L., Gascon, T., Gibon, F., Guiro, I., Ingatan, A., Kempf, J., Kotchoni, D. O. V., Lawson, F. M. A., Leauthaud, C., Louvet, S., Mason, E., Nguyen, C. C., Perrimond, B., Pierre, C., Richard, A., Robert, E., Romá-Cascón, C., Velluet, C., and Wilcox, C.: AMMA-CATCH, a Critical Zone Observatory in West Africa Monitoring a Region in Transition, Vadose Zone J., 17, 180062, https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2018.03.0062, 2018.

Gbobaniyi, E., Sarr, A., Sylla, M. B., Diallo, I., Lennard, C., Dosio, A., Dhiédiou, A., Kamga, A., Klutse, N. A. B., Hewitson, B., Nikulin, G., and Lamptey, B.: Climatology, annual cycle and interannual variability of precipitation and temperature in CORDEX simulations over West Africa, Int. J. Climatol., 34, 2241–2257, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.3834, 2014.

Gounou, A., Guichard, F., and Couvreux, F.: Observations of Diurnal Cycles Over a West African Meridional Transect: Pre-Monsoon and Full-Monsoon Seasons, Bound.-Lay. Meteorol., 144, 329–357, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10546-012-9723-8, 2012.

Goyens, C., Lauwaet, D., Schröder, M., Demuzere, M., and Van Lipzig, N. P. M.: Tracking mesoscale convective systems in the Sahel: Relation between cloud parameters and precipitation, Int. J. Climatol., 32, 1921–1934, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.2407, 2012.

Grabowski, W. W., Bechtold, P., Cheng, A., Forbes, R., Halliwell, C., Khairoutdinov, M., Lang, S., Nasuno, T., Petch, J., Tao, W. K., Wong, R., Wu, X., and Xu, K. M.: Daytime convective development over land: A model intercomparison based on LBA observations, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 132, 317–344, https://doi.org/10.1256/qj.04.147, 2006.

Hannak, L., Knippertz, P., Fink, A. H., Kniffka, A., and Pante, G.: Why do global climate models struggle to represent low-level clouds in the west african summer monsoon?, J. Climate, 30, 1665–1687, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0451.1, 2017.

Hersbach, H., Bell, B., Berrisford, P., Hirahara, S., Horányi, A., Muñoz-Sabater, J., Nicolas, J., Peubey, C., Radu, R., Schepers, D., Simmons, A., Soci, C., Abdalla, S., Abellan, X., Balsamo, G., Bechtold, P., Biavati, G., Bidlot, J., Bonavita, M., De Chiara, G., Dahlgren, P., Dee, D., Diamantakis, M., Dragani, R., Flemming, J., Forbes, R., Fuentes, M., Geer, A., Haimberger, L., Healy, S., Hogan, R. J., Hólm, E., Janisková, M., Keeley, S., Laloyaux, P., Lopez, P., Lupu, C., Radnoti, G., de Rosnay, P., Rozum, I., Vamborg, F., Villaume, S., and Thépaut, J. N.: The ERA5 global reanalysis, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 146, 1999–2049, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803, 2020.

Hill, P. G., Allan, R. P., Chiu, J. C., Bodas-Salcedo, A., and Knippertz, P.: Quantifying the contribution of different cloud types to the radiation budget in southern West Africa, J. Climate, 31, 5273–5291, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-17-0586.1, 2018.

Johnson, R. H., Rickenbach, T. M., Rutledge, S. A., Ciesielski, P. E., and Schubert, W. H.: Trimodal characteristics of Tropical convection, J. Climate, 12, 2397–2418, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(1999)012<2397:tcotc>2.0.co;2, 1999.

Kalthoff, N., Lohou, F., Brooks, B., Jegede, G., Adler, B., Babić, K., Dione, C., Ajao, A., Amekudzi, L. K., Aryee, J. N. A., Ayoola, M., Bessardon, G., Danuor, S. K., Handwerker, J., Kohler, M., Lothon, M., Pedruzo-Bagazgoitia, X., Smith, V., Sunmonu, L., Wieser, A., Fink, A. H., and Knippertz, P.: An overview of the diurnal cycle of the atmospheric boundary layer during the West African monsoon season: results from the 2016 observational campaign, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 2913–2928, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-2913-2018, 2018.

Kniffka, A., Knippertz, P., and Fink, A. H.: The role of low-level clouds in the West African monsoon system, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 1623–1647, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-1623-2019, 2019.

Knippertz, P., Fink, A. H., Schuster, R., Trentmann, J., Schrage, J. M., and Yorke, C.: Ultra-low clouds over the southern West African monsoon region, Geophys. Res. Lett., 38, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GL049278, 2011.

Knippertz, P., Coe, H., Chiu, J. C., Evans, M. J., Fink, A. H., Kalthoff, N., Liousse, C., Mari, C., Allan, R. P., Brooks, B., Danour, S., Flamant, C., Jegede, O. O., Lohou, F., and Marsham, J. H.: The DACCIWA project: Dynamics–Aerosol–Chemistry–Cloud Interactions in West Africa., B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 96, 1451–1460, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-14-00108.1, 2015.

Kosmopoulos, P. G., Kazadzis, S., Lagouvardos, K., Kotroni, V., and Bais, A.: Solar energy prediction and verification using operational model forecasts and ground-based solar measurements, Energy, 93, 1918–1930, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2015.10.054, 2015.

Kuwonu, F.: Harvesting the sun. Scaling up solar power to meet Africa's energy needs, Africa Renew, available at: https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/april-2016/harvesting-sun (last access: 15 May 2020), 2016.

Liou, K. N.: An introduction to atmospheric radiation, Elsevier Science, San Diego, CA, USA, 2002.

Liu, Y., Wu, W., Jensen, M. P., and Toto, T.: Relationship between cloud radiative forcing, cloud fraction and cloud albedo, and new surface-based approach for determining cloud albedo, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 7155–7170, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-7155-2011, 2011.

Lohou, F., Kalthoff, N., Adler, B., Babić, K., Dione, C., Lothon, M., Pedruzo-Bagazgoitia, X., and Zouzoua, M.: Conceptual model of diurnal cycle of low-level stratiform clouds over southern West Africa, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 2263–2275, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-2263-2020, 2020.

Mace, G. G. and Zhang, Q.: The CloudSat radar-lidar geometrical profile product (RL-GeoProf): Updates, improvements, and selected results, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 119, 9441–9462, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013JD021374, 2014.

Mallet, M., Tulet, P., Serça, D., Solmon, F., Dubovik, O., Pelon, J., Pont, V., and Thouron, O.: Impact of dust aerosols on the radiative budget, surface heat fluxes, heating rate profiles and convective activity over West Africa during March 2006, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 7143–7160, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-7143-2009, 2009.

Marsham, J. H., Dixon, N. S., Garcia-Carreras, L., Lister, G. M. S., Parker, D. J., Knippertz, P., and Birch, C. E.: The role of moist convection in the West African monsoon system: Insights from continental-scale convection-permitting simulations, Geophys. Res. Lett., 40, 1843–1849, https://doi.org/10.1002/grl.50347, 2013.

Mathon, V., Laurent, H., and Lebel, T.: Mesoscale convective system rainfall in the Sahel, J. Appl. Meteorol., 41, 1081–1092, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0450(2002)041<1081:MCSRIT>2.0.CO;2, 2002a.

Mathon, V., Diedhiou, A., and Laurent, H.: Relationship between easterly waves and mesoscale convective systems over the Sahel, Geophys. Res. Lett., 29, 12–15, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001GL014371, 2002b.

Moner-Girona, M., Bódis, K., Korgo. B., Huld, T., Kougias, I., Pinedo-Pascua, I., Monforti-Ferrario, F., and Szabó, S.: Mapping the least-cost option for rural electrification in Burkina Faso – Scaling-up renewable energies, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, https://doi.org/10.2760/900097, 2017.

Monerie, P. A., Sanchez-Gomez, E., Gaetani, M., Mohino, E., and Dong, B.: Future evolution of the Sahel precipitation zonal contrast in CESM1, Clim. Dynam., 55, 2801–2821, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-020-05417-w, 2020.

MPEER: Ministre du Pétrole, de l'Energie et des E. R.: Rapport d'Activités MPEER 2018, available at: http://www.mpeder.ci/uploads/documents/rapports/RAPPORT_D_ACTIVITES_ MPEER_2018.pdf (last access: 21 March 2020), 2019.

Nicholson, S. E.: A revised picture of the structure of the “monsoon” and land ITCZ over West Africa, Clim. Dynam, 32, 1155–1171, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-008-0514-3, 2009.

Nicholson, S. E.: The West African Sahel: A Review of Recent Studies on the Rainfall Regime and Its Interannual Variability, ISRN Meteorol., 2013, 1–32, https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/453521, 2013.

Nicholson, S. E.: The ITCZ and the seasonal cycle over equatorial Africa, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 99, 337–348, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-16-0287.1, 2018.

Parker, D. J., Burton, R. R., Diongue-Niang, A., Ellis, R. J., Felton, M., Taylor, C. M., Thorncroft, C. D., Bessemoulin, P., and Tompkins, A. M.: The diurnal cycle of the West African monsoon circulation, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 131, 2839–2860, https://doi.org/10.1256/qj.04.52, 2005.

Pedruzo-Bagazgoitia, X., de Roode, S. R., Adler, B., Babić, K., Dione, C., Kalthoff, N., Lohou, F., Lothon, M., and Vilà-Guerau de Arellano, J.: The diurnal stratocumulus-to-cumulus transition over land in southern West Africa, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 2735–2754, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-2735-2020, 2020.

Redelsperger, J.-L., Thorncroft, C. D., Diedhiou, A., Lebel, T., Parker, D. J., and Polcher, J.: African Monsoon Multidisciplinary Analysis: An International Research Project and Field Campaign, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 87, 1739–1746, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-87-12-1739, 2006.

Schrage, J. M. and Fink, A. H.: Nocturnal continental low-level stratus over tropical west africa: Observations and possible mechanisms controlling its onset, Mon. Weather Rev., 140, 1794–1809, https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR-D-11-00172.1, 2012.

Schuster, R., Fink, A. H., and Knippertz, P.: Formation and Maintenance of Nocturnal Low-Level Stratus over the Southern West African Monsoon Region during AMMA 2006, J. Atmos. Sci., 70, 2337–2355, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-12-0241.1, 2013.

Stein, T. H. M., Parker, D. J., Delanoë, J., Dixon, N. S., Hogan, R. J., Knippertz, P., Maidment, R. I., and Marsham, J. H.: The vertical cloud structure of the West African monsoon: A 4 year climatology using CloudSat and CALIPSO, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 116, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JD016029, 2011.

Storer, R. L. and Van den Heever, S. C.: Microphysical processes evident in aerosol forcing of tropical deep convective clouds, J. Atmos. Sci., 70, 430–446, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-12-076.1, 2013.

Sultan, B. and Janicot, S.: Abrupt shift of the ITCZ over West Africa and intra-seasonal variability, Geophys. Res. Lett., 27, 3353–3356, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999GL011285, 2000.

Sultan, B. and Janicot, S.: The West African monsoon dynamics. Part II: The “preonset” and “onset” of the summer monsoon, J. Climate, 16, 3407–3427, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(2003)016<3407:TWAMDP>2.0.CO;2, 2003.

Sultan, B., Janicot, S., and Diedhiou, A.: The West African monsoon dynamics. Part I: Documentation of intraseasonal variability, J. Climate, 16, 3389–3406, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(2003)016<3389:TWAMDP>2.0.CO;2, 2003.

Thorncroft, C. D., Nguyen, H., Zhang, C., and Peyrill, P.: Annual cycle of the West African monsoon: regional circulations and associated water vapour transport, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 137, 129–147, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.728, 2011.

Turner, D. D., Vogelmann, A. M., Austin, R. T., Barnard., J. C., Cady-Pereira., K., Chiu, J. C., Clough., S. A., Flynn, C., Khaiyer, M. M., Liljegren, J., Johnson, K., Lin, B., Long, C., Marshak, A., Matrosov., S. Y., Mcfarlane., S. A., Miller, M., Min, Q., Minnis, P., O'Hirok, W., Wang, Z., and Wiscombe, W.: Thin liquid water clouds, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 88, 177–190, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-88-2-177, 2007.

van der Linden, R., Fink, A. H., and Redl, R.: Satellite-based climatology of low-level continental clouds in southern West Africa during the summer monsoon season, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 120, 1186–1201, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JD022614, 2015.

Vizy, E. K. and Cook, K. H.: Understanding the summertime diurnal cycle of precipitation over sub-Saharan West Africa: regions with daytime rainfall peaks in the absence of significant topographic features, Clim. Dynam, 52, 2903–2922, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-018-4315-z, 2019.

World Bank: This Is What It's All About: Boosting Renewable Energy in Africa, World Bank Gr, available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2019/02/26/this-is-what-its-all-about-boosting-renewable-energy-in-africa (last access: 8 February 2020), 2019.

Yang, G.-Y. and Slingo, J.: The Diurnal Cycle in the Tropics, Mon. Weather Rev., 129, 784–801, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0493(2001)129<0784:TDCITT>2.0.CO;2, 2001.

Zouzoua, M., Lohou, F., Assamoi, P., Lothon, M., Yoboue, V., Dione, C., Kalthoff, N., Adler, B., Babić, K., and Pedruzo-Bagazgoitia, X.: Breakup of nocturnal low-level stratiform clouds during southern West African Monsoon Season, Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-2020-602, in review, 2020.

Detailed documentation at: https://confluence.ecmwf.int/display/CKB/ERA5+data+documentation, last access: 18 September 2019.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Data and methods

- Temporal distribution of the occurrence of daytime LLCs

- Synoptic conditions related to the occurrence of daytime LLCs

- Attenuation of incoming shortwave radiation during LLC occurrence

- Conclusions

- Appendix A: Vertical profiles of cloud hydrometeor content during LLC occurrence

- Appendix B: Specific humidity associated with LLC occurrence and potential temperature before and after LLC formation

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Data and methods

- Temporal distribution of the occurrence of daytime LLCs

- Synoptic conditions related to the occurrence of daytime LLCs

- Attenuation of incoming shortwave radiation during LLC occurrence

- Conclusions

- Appendix A: Vertical profiles of cloud hydrometeor content during LLC occurrence

- Appendix B: Specific humidity associated with LLC occurrence and potential temperature before and after LLC formation

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement